How a Benton Harbor merchant helped a family escape from the Nazis

- Mike Eliasohn

- Aug 7, 2022

- 9 min read

Updated: Aug 23, 2022

Anne Schmitz lives in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, but if it wasn’t for the efforts of the owner of a men’s clothing store in Benton Harbor, Michigan, to rescue her grandparents and their children from Nazi-occupied Austria, she and her brother might never have been born.

Curiosity about her family’s past led her to do some research. She wrote the story of what she learned in the form of a letter to the Hennes family. (Photos for this article and copies of documents were provided by Anne.)

(Editing and some additional content by Michiana Jewish Historical Society board member Mike Eliasohn)

Dear children and grandchildren and great grandchildren (and so on) of Oscar Hennes,

I write to tell you that we are step-cousins, co-descendants. I write to thank your bloodline for my life. It was like this:

In 2019 I found three documents in my late mother’s shoebox filing system:

October 12, 1938: The sworn affidavit of Oscar Hennes, a clothier in Benton Harbor, Michigan, states that that he was born in the USA and that he promises the U.S. government that he will receive and take care of Moritz Schmitz, his wife Frieda and their children Heinrich and Gertrude — who, in less than 14 years would become my grandparents, father and aunt — and “I will at no time allow them to … become public charges upon any community or municipality”

(Note: In various documents, his name also is spelled “Moriz” and “Morritz.”)

Hennes listed his assets and income.

March 15, 1939: a second affidavit required by U.S. authorities, in which Oscar Hennes reiterates in detail, that he, owner of a menswear store in a small town in Michigan, would make sure these “friends” of his from Vienna would have “food, clothing ,shelter and pocket money until they become self-supporting.”

Oct. 17, 1940: The third document is a copy of a letter from Oscar Hennes to my grandfather, Moritz, on the Hennes, The Store for Men and Boys store stationery. “I am very happy that you have arrived in our beautiful country,” he wrote.

He advised the family to stay in New York City. “In a big city, where you are, your chances are much greater on account of the great mass of population, including people of your own type.”

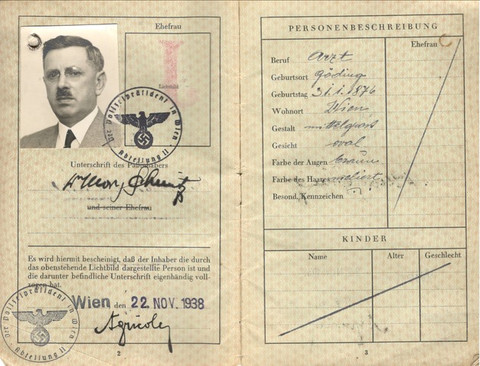

The 1938 Nazi passports of Frieda and Moritz Schmitz. They and their children then obtained visas to move to Great Britain in February 1939 and came there the following month. After Germany invaded Austria in March 1938, Austria was erased as a country, becoming part of the Third Reich, so these passports were issued by Germany.

In contrast, he wrote, Benton Harbor was a city of 15,000 and “the few refugees that are here are having difficulty, even though relatives have taken them in.”

(Eliasohn: That comment suggests other Jews in the Benton Harbor area also may have sponsored families to enable them to flee the Nazis in Europe.)

He signed the letter: “With my best wishes for your success. Yours very truly, Oscar Hennes.”

(Eliasohn: Moritz and Frieda lived in New York City until their deaths. Anne Schmitz has found nothing to indicate that they and Oscar Hennes ever met.

Nor is it known how Hennes got connected with the Schmitz family as its sponsor. Was there possibly a Jewish organization in the United States, maybe through articles in Jewish publications, which sought sponsors and Hennes read one of the articles?

During the time Hennes sponsored the Schmitz family coming to the U.S., he and his family were members of Temple Beth-El, which was Reform and one of three Jewish congregations in Benton Harbor.)

Finding this trail delighted me. I am of the first generation born in North America (as was Mr. Hennes) and any attempt to trace my lineage had been blocked by the torn up rubble of the 19th and 20th Centuries and likely even earlier troubled times.

My sense has been that my people have been on the move for so long that our records have either been destroyed in the fires of war or tangled in languages and alphabets unknown to me. Each generation on the move has left its stories behind.

Leaving is in our DNA.

These letters showed me that arriving is also in my DNA. I immediately began to search for the descendants of Oscar Hennes in order to thank them for my very life.

LEFT: Frieda and Moritz Schmitz attended the graduation of their son, Heinrich/Henry, from Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, in 1949, nine years after the family came to the United States and four years since the end of World War II, during which Henry served in the Army’s Intelligence Service and attained the rank of captain. He eventually earned a Ph.D and had a career as a research chemist.

RIGHT: Gertrude “Trudy” Schmitz in the 1930s, when she and her family still lived in Austria. She was 30 when they came to the United States in 1940. She became a dress designer in New York City, then retired to Florida. She died in 2003.

When Oscar swore in his first affidavit in 1938, my forebears were watching the storm clouds gather.

The Munich Agreement by Germany, Great Britain, France and Italy that permitted German annexation of the Sudetenland in western Czechoslovakia had been signed two weeks earlier (Sept. 30). Kristallnacht (Nov. 9-10) was still four weeks in the future.

The Schmitz family began to look for a place that would receive them. Very few countries were accepting Jewish refugees.

Three days before Oscar swore in his second affidavit, the German army rolled into Austria, on March 12, 1938, annexing the country to the Third Reich. Life in Vienna was suddenly extremely difficult for Jews. It became urgent that they leave.

Still, the U.S. authorities took their time, as bureaucracies do. There was a benefit to British Prime Minister Chamberlain’s signing of the Munich Agreement, for which he was widely criticized and called a fool for trusting Hitler. As my mother always emphasized, it bought the British time to prepare for war. Resistance was strong against engaging in another brutal war so soon after World War I and the country had to re-arm.

Immediately, the munitions factories began to hire workers and domestic servants and restaurant staff flocked to those jobs with their higher pay and weekends off.

The shortage of servants and waiters at last opened Britain to the desperate Jews of Europe. The four Schmitzes managed to get temporary permits to reside in England and found jobs and lodging.

The visas to admit the family to the UK were dated Feb. 21,1939. A British stamp on their passports indicate they entered the UK on March 17.

After war was declared in September of 1939 and the German army seemed to be marching unstoppably towards the European coast, the British began to fear invasion and that there might be enemy spies hiding among the thousands of German-speaking Jewish refugees.

By May and June of 1940, most of the men (including Moritz and Heinrich) and some women had been interned in camps and many were being sent to Canada and Australia for prolonged imprisonment.

Some time in late July or early August of 1940, the visas were finally issued for the Schmitz family to embark for the U.S.

Heinrich, my future father, wrote to his high school girlfriend, Edith Schachter (born April 17, 1920), who was working as a maid in London. He suggested she might be added to the visa for his family. This note was his marriage proposal.

The wedding was arranged and two Scotland Yard officers accompanied Heinrich and his father Moritz to the ceremony with a justice of the peace, then joined the wedding party for breakfast before returning their charges to the lock-up.

The Americans declined permission for the new bride to emigrate and so the Schmitzes went to the United States and my future mother spent the war years in London, but now as a married woman. (The “newlyweds” had a little honeymoon when Heinrich, now Henry, came to England with the U.S. Army in the spring of 1944 to prepare for the D-Day Invasion, which took place on June 6th. He was sent to France two days later.)

The couple was finally united in the U.S. in April 1945.

My mother used to joke that the secret to a successful marriage was not to live together for the first five years.

Without Oscar Hennes, there would not have been that hasty proposal and there might not have been a “me.”

Records from the Statue of Liberty – Ellis Island Foundation show the family departed on the ship Cameronia from Glasgow, Scotland, on Sept. 1, 1940, and arrived in New York City on Sept. 10.

When they arrived, Moritz was 64 years old; Frieda was 55; Gertrude was 30; and Heinrich was 23.

Typically, arriving refugees do two things: They hit the ground running, transforming themselves to fit the new country and find a way to make a living. They also discard and forget the old ways that disadvantage their survival. After they were settled in New York, my father wrote a thank-you letter to Mr. Hennes. He responded by sending a suit to my father, making good on his promise in the 1939 affidavit to provide clothing “until they become self-supporting.”

So I am reasonably certain that after my father wrote to thank Oscar for the suit, there was no more contact.

Tales similar to the one I have told must have been played out by the thousands during that period. How many of us descendants know these stories? The closing words of the last document seem to be intended as a blessing and a release for both parties. The pretense of friendship was discarded. All were free to be strangers.

Yet to me the discovery of the connection between our families gives me a sense of a web of relatedness that is not constrained by lineal descent, but rather is energized by entanglements beneath the surface.

And so, your ancestor’s kindness, his courage, his small lie to the authorities claiming an existing friendship with my people, has woven us together into a family of shared dimensions in ‘this beautiful country’. We may never meet, but thank you for your part in the fabric of my world.

In 2019, I spoke with Oscar’s granddaughter, Amy Hennes Stein, who was born in 1958. She had never heard of her grandfather’s good deed in sponsoring the Schmitz family, but was not surprised that he would do such a thing.

She assured me that his actions were in keeping with his personality and sense of service (which show up in the newspaper accounts of his volunteer work in Benton Harbor). She also was certain that he would have consulted with his wife, Lillian, on the matter of his generous and risky offer.

I think it was a very brave thing to promise to the U.S. government to accept responsibility for strangers. Who knew how they would turn out?

After my grandparents, future father and aunt had arrived safely and sent thank-you letters, they began the difficult task of assimilating into America and did not keep in touch.

My grandfather, Moritz Schmitz, who was a physician in Vienna, found work as a masseur until he learned enough English to write and pass his exams to qualify as a doctor in New York.

Moritz and Frieda lived in New York City until they died. (Moritz’s funeral was Jan, 2, 1951, so I assume he died on Jan. 1.)

My grandmother, Frieda, who had been born into a family that was wealthy before World War I, took a job sewing in a Garment District shop. She died in the summer of 1956.

My future father, Henry Schmitz, took odd jobs until he enlisted in the Army and served as a translator in the Military Intelligence Service. After the war, he studied chemistry under the GI Bill, earned a Ph.D and went on to a career as a research chemist. He died Feb. 8, 1999.

My Aunt Trudy, who in the early 1940s married an immigrant from Rome, Italy, had a career as a dress designer in New York and a long active retirement in Florida, where she volunteered with the opera and symphony. She died Feb. 7, 2003.

(Henry and Edith and their children David and Anne, born in 1949 and 1952 respectively, lived most of their years as a family in Syracuse, N.Y. )

Anne Morris Schmitz has lived in Canada since 1971, starting in British Columbia and in Ottawa, Ontario, since the late 1980s. Her son, Skye Sheele, born in 1974, lives in British Columbia.

Her brother, David Ruben Schmitz, has lived in London, England, since about 1970 and recently obtained/reclaimed Austrian citizenship for himself and his children, Charlotte, born in 2007 and Olivia, born in 2013.

So the Schmitz family did not turn out to be a burden on the Hennes family.

The Hennes Co. was started in 1893 in downtown Benton Harbor by Meier Hennes, who sold it to his sons, Oscar and Lewis, shortly after the end of World War I, when Oscar returned home from serving in the Navy. Lewis left the business in 1925.

The company was in three locations in downtown Benton Harbor until moving to St. Joseph In 1973.

Oscar died in 1971 at age 75. His son, Richard, who joined the business in 1953, and his wife, Laya, ran it until it closed in January 1997, at its second location in St. Joseph. He died in 2015.

The one constant through its 104 years in business was men’s clothing. The company stopped selling boys clothes in the late 1940s, then Laya added women’s attire in 1954.

(By Mike Eliasohn. Information from various articles in The Herald-Palladium newspaper files.)